On June 6, 1944, Pvt. Linaburg — U.S. Army, 101st Airborne, 502nd Parachute Infantry Regiment — stepped out of the plane and into the void. He was 21.

Meanwhile, Albert H. Small was thousands of miles away from the beaches of Normandy. He was a young Navy sailor serving on a light cruiser in the Pacific.

Today, Small is a 93-year-old D.C. developer and philanthropist who thinks all Americans should remember what was achieved during the war. And he thinks the defeat of fascism can be encapsulated in what happened on a single day: June 6, 1944.

"That was the climax of the war," Small said. "If we hadn't been successful on D-Day invading Germany, we'd have lost the war."

Robert G. Perry, chairman of the National Trust for the Humanities, has known Small for 30 years. “He thinks no American should forget about the sacrifices on this one day,” Perry said.

But how to communicate that? Small had an idea.

“One of his mantras was that the government should lease 747s and just shuttle Americans to Normandy,” Perry said.

I love that notion — a fleet of 747s depositing Americans in France — but Perry convinced his friend that another approach might be more workable.

And thus was born the Albert H. Small Normandy Institute, launched in 2011. Each year, 15 high school juniors from across the United States are selected for the program. The students each pick an American from their area who is buried in Normandy and, with the help of their teachers, do extensive research on his life.

In June, the students and their teachers are brought to Washington for five days. They stay at George Washington University — Small’s alma mater — and visit such sights as the World War II Memorial and Arlington Cemetery. They have dinner with Small and Mortimer Caplan, a retired tax lawyer who was a beachmaster on D-Day, guiding landing craft ashore.

Then they fly to France for eight days. The first thing they do in Normandy is retrace the steps their fallen hero took.

“When they look at those cliffs — Omaha Beach; any of them — it’s overwhelming,” said Perry.

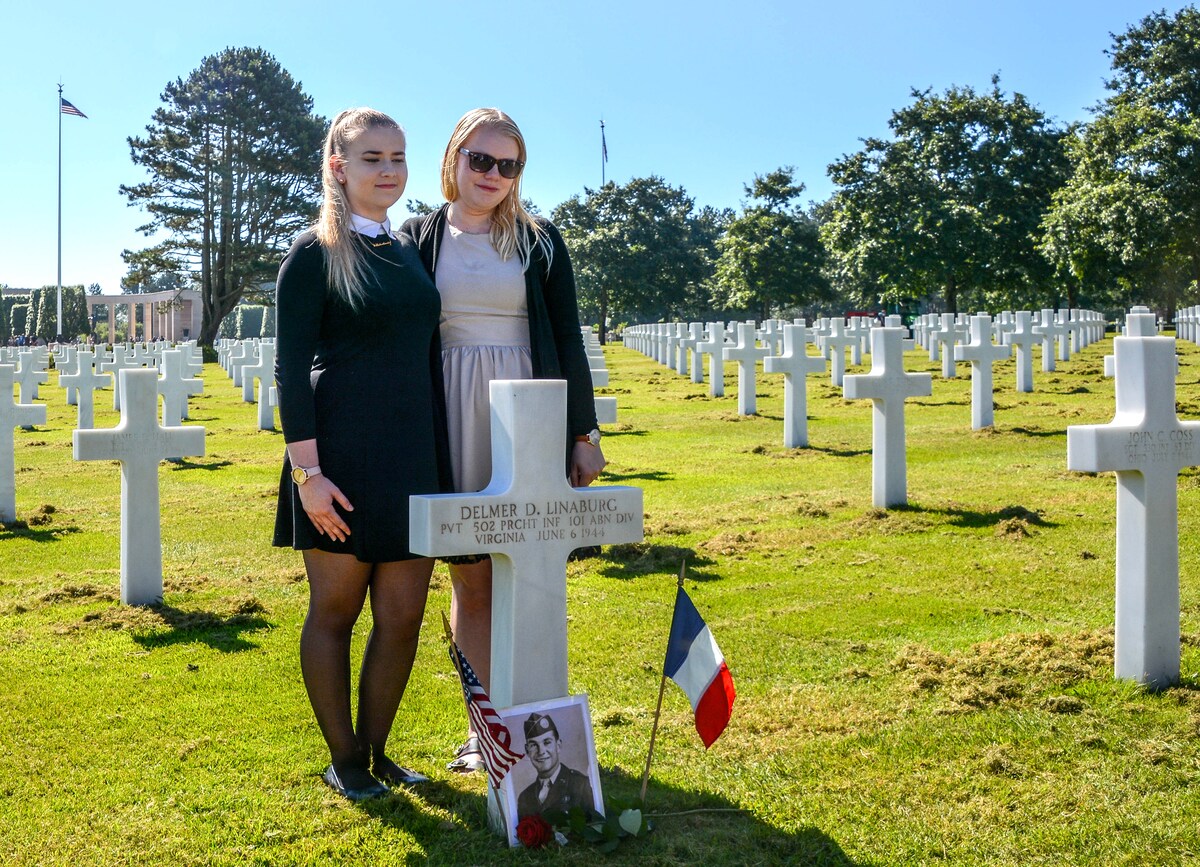

They find their service member’s grave among the more than 9,000 Americans buried at Normandy American Cemetery and deliver a eulogy.

Last year, Haley Broga from Loudoun County, Va., was one of the students. She went to Normandy with her Freedom High School history teacher, Kate Corrado. Together, they had researched Pvt. Linaburg, who was killed by German machine-gun fire while trying to secure bridges east of the beaches.

They interviewed one of Linaburg’s nieces. She’d never met her uncle, but she shared stories she’d heard about him, how he had a sense of humor and was a hit with girls, how he’d dropped out of high school to work in an orchard and provide for his family.

“I’ve been thinking about that a lot as I’m getting ready to graduate,” said Broga, 18. “It makes me feel very grateful for the opportunities I’ve had that he didn’t have.”

The budget for the Albert H. Small Normandy Institute is about $350,000 a year, Perry said. It’s funded entirely by Small, who has also underwritten the Albert H. Small Washingtoniana Collection at GWU.

This week, Broga graduates from Freedom High. In the fall she’ll start at James Madison University on an Air Force ROTC scholarship. She’s majoring in physics and plans on becoming an Air Force officer.

Last June, Broga walked to Delmer Linaburg, who rests in Grave 25 in Row 20 of Plot D at Normandy American Cemetery in Colleville-sur-Mer, France.

“The sun was so bright,” she said. “The sky was totally, purely blue.”

Roses bloomed nearby.

“So it was really beautiful,” Broga said. “I was really quite overcome with emotion upon seeing it.”

She knew Pvt. Linaburg’s family had never been able to travel to France to visit their son, their brother, their uncle. But she was there now, with greetings from home and a promise that she’d never forget him.