WILDROSE — The Wildrose Senior Citizens Center quickly filled up on Sunday afternoon as members of the community gathered to learn about one of their own.

Kari Hall, a teacher at Williston High School, and one of her students, MaKenna Vigness, returned to the United States a few weeks ago after having spent time in France to learn more about World War II, Normandy, and Lawrence Woodside.

Woodside is one of three veterans with ties to Williams County who were killed in World War II and buried in the Normandy American Cemetery, not far from Omaha Beach in Normandy, France, where 80 years ago this year, D-Day unfolded. Woodside, specifically, grew up in Wildrose.

About 50 people, incidentally around half of the town's population, crowded into the center to hear Hall and Vigness' presentation, leaving Wildrose's mayor Marlyn Vatne helping to assemble enough chairs for the attendees.

Lawrence Woodside of Wildrose served with the 17th Armored Engineer Battalion until his death in Normandy, France, on Aug. 24, 1944. Woodside is one of three men with Williams County connections to be buried in the Normandy American Cemetery.

Hall and Vigness's trip, which started with a week in Washington, D.C., and then a week in France, was made possible through the Albert H. Small 2024 Normandy Institute through George Washington University. They were among fifteen teacher-student pairs — Hall and Vigness were the first from North Dakota — tasked with "telling the history of Normandy" through localized stories. In the case of Hall and Vigness, it is through Woodside; their project focuses on his military service, his life before, and his unit's history after Woodside's death.

Their information is being compiled into a biography, which Hall and Vigness will submit to the Normandy American Cemetery. There, the information will be readily available for anyone looking for information on the Wildrose soldier.

Connection with the project

It was about one and a half years ago while attending a National Social Studies Conference that Hall learned about the Albert H. Small Normandy Institute. She spent a half hour talking to a representative, learning more about the program, which helps student-teacher teams learn more about the D-Day Campaign of 1944.

The deadline had passed for that year, but the following year, Hall signed up.

This last fall when the school year began, Hall visited with her U.S. history students to talk about what historical eras they were interested in. While she was asking in order to focus her coursework, she had an ulterior motive: she wanted to see which student to invite on the trip. When Vigness, then a junior, expressed her interest in World War II, Hall knew she was the one.

World War II interested Vigness because of "how it was fought," she said. "They had a lot more high-tech weapons" when compared to World War I. Her father is also interested in World War II and they had relatives who fought in the war, she noted.

Through the Normandy Institute, Hall and Vigness spent four days in Washington, D.C., five or six days in the Normandy region, and two days in Paris.

"It was amazing, it was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity," Vigness said. (This was her first time visiting Washington, D.C., as well as leaving the country.) "I'm real glad Ms. Hall picked me."

When it came to selecting a veteran to highlight, Hall said that it came down to finding one who lived as closest to Williston as possible. She immediately went to work finding that soldier. And then she found Woodside.

As soon as she knew his name and his connection to Williams County and Wildrose, "I started checking genealogy sites to connect with any relatives," Hall explained. The name Woodside didn't immediately give her much information, but after learning about his sisters and finding their married names, that opened doors. Hall made a connection with a name, Hickel, the married name of Lawrence's older sister, Mabel. Hall recalled teaching two generations, a father and son, with the name Hickel. She reached out to the father and asked if there was any connection with a Mabel Woodside Hickel and if there were any relatives that could help with information. He suggested Wilma (Hickel) Hillstead, who was Mabel's daughter and Lawrence's niece.

Hillstead, who lives in Williston, is the only living relative who could remember her uncle; she was eight years old when he was killed in the war. Hall and Vigness found Hillstead to be an important resource in their biography of Woodside, which is currently 19 pages long — a feat which grew from having limited information about Woodside.

"We just had such a project in front of us," Hall said. "We got excited the more we found. As soon as Makenna found his military records, then we knew more of the details of what direction to go to." Vigness also located Woodside's draft card. "We knew some details, but we didn't know how to string them all together."

When the two met with Hillstead the first time, "we went to her home in Williston and got to know her a bit," Hall said. "You don't want to ask questions without knowing any context."

The emotional connection with their subject started when Hillstead explained that a local service was not held for Woodside in Wildrose.

"Just that open-endedness that this was never addressed, the aspect that anyone stands at a gravesite and tells of who they are, you want to do it well," Hall said, adding that she put the pressure on her own shoulders to know his story as well as possible.

While they were in Normandy, they had the chance to offer Woodside that service at his grave at the Normandy American Cemetery.

"The Normandy region is gorgeous," Vigness said, adding that "it makes you think of what happened. How could something so beautiful have something so cruel happen (in it)?"

With the information available to them, Vigness took snippets from the biography to offer Woodside the eulogy that never happened, now almost 80 years after his death.

"Leading up to delivering the eulogy at the cemetery, I didn't think I was going to cry at all," Vigness said. However, after talking with Hillstead, Vigness began to feel the connection.

"He had family. He had people who loved him," Vigness said.

And he made the ultimate sacrifice, she added.

Being at his gravestone and knowing that Woodside never had a ceremony or a eulogy read, it "made it a lot deeper for me," Vigness said.

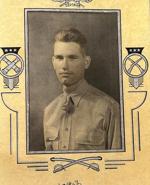

Lawrence Woodside (back row, right) poses with his sisters and parents in a family photo.

A Wildrose boy

Woodside was born on Oct. 9, 1910, in Ray. Sometime after his birth, the family moved to Wildrose, a city in its infancy about 20 miles north of Ray. It was in Wildrose where his father Alvin served as a postman for almost 30 years.

The family — Alvin, his wife Bertha (Krause), and their six children; Lawrence was the only son — made their home in the old Wildrose school which was converted into a home when a separate traditional brick school, which closed in 2006, was built.

After graduating from Wildrose High School in 1929, Woodside found himself west. While attempting to enlist in the U.S. Navy around June 1934, Woodside was deemed ineligible due to varicose veins in his legs. He found work in Illinois and later lived in Idaho near the Canadian border. It was near there, in Spokane, Washington, when Lawrence enlisted in the U.S. Army on Feb. 21, 1941.

The varicose veins were either cured or weren't a problem by this time. Woodside's enlistment in the military happened "months before the first action against the U.S.," Pearl Harbor, took place.

In the Army now

Woodside served with the 17th Armored Engineer Battalion of the 2nd Armored Division, Company A. Gen. George S. Patton, the U.S. Army general who commanded the Seventh Army in the Mediterranean Theater of World War II and the Third Army in France and Germany after the Allied invasion of Normandy in June 1944, was in charge of training.

The battalion was stationed in North Africa — in the only surviving letter home, Woodside was vague about his location, noting in a P.S.: "somewhere in Africa" — before helping to liberate Sicily (as part of Operation Husky) in July 1943 and then moving on to England to prepare for Operation Overlord, the codename for the Battle of Normandy.

Woodside wasn't in Normandy on D-Day; he arrived on Omaha Beach two days later, having been in England 'prepping for the port," Hall said.

"They spent June 9 de-waterproofing vehicles and checking assembly area for mines then set up a bivouac at T706834 MOSLES," Woodside's biography noted of his battalion's actions after arriving in Normandy.

A log journal of the battalion catalogues the 17th Armored Engineer Battalion's daily routines, which included Operation Cobra, an offensive attack seven weeks after D-Day. The journal, at least in regard to Woodside, ended on Aug. 24, 1944, when Woodside died from shrapnel wounds.

As noted in the Wildrose Mixer when announcing his death, Woodside was the first local World War II soldier to die in action overseas. "True, several local men have lost their lives, but these were accidental and in this country while training," the Sept. 14, 1944, issue of the newspaper stated.

MaKenna Vigness rubs sand from Omaha Beach on the cross marking the burial spot of Lawrence Woodside, a soldier from Wildrose who died in the Battle of Normandy in 1944.

The return home

The teacher-student pair from Williston returned stateside, their internal filing cabinets filled with information about Woodside, a gentleman who a few weeks before they knew nothing about.

The experience left them emotional — particularly Vigness as she delivered the eulogy for Woodside at the French cemetery; Hall while she spoke in Wildrose on Sunday. The name that first appeared to them in records and on the grave marker was, over time, fleshed out to reveal Woodside, the man.

"I believe every soldier's story needs to be heard, no matter how big or small," Vigness said. "We need to remember those who sacrifice their lives (as its) the reason we hold the freedoms we do today."

Woodside's biography has a little fine-tuning to be done on it before it can be submitted, Hall said. "We're hoping to be done in the next couple weeks."

There is still the matter of a check issued to the Woodside family that Hall wants to investigate further. The check amount, $9,000, seems like quite a lot, Hall noted, adding that she wants to figure out how death benefits worked in the times of World War II. "I'm trying to verify why that check has that certain amount."

While driving home from Wildrose after her presentation on Sunday afternoon, Hall said that she had time to reflect on the situation.

"Sometimes, we take our freedoms for granted," she said Monday, adding that there are some, like Woodman, who gave their all.